git.nowhere.moe is going underground!

git.nowhere.moe is going underground!

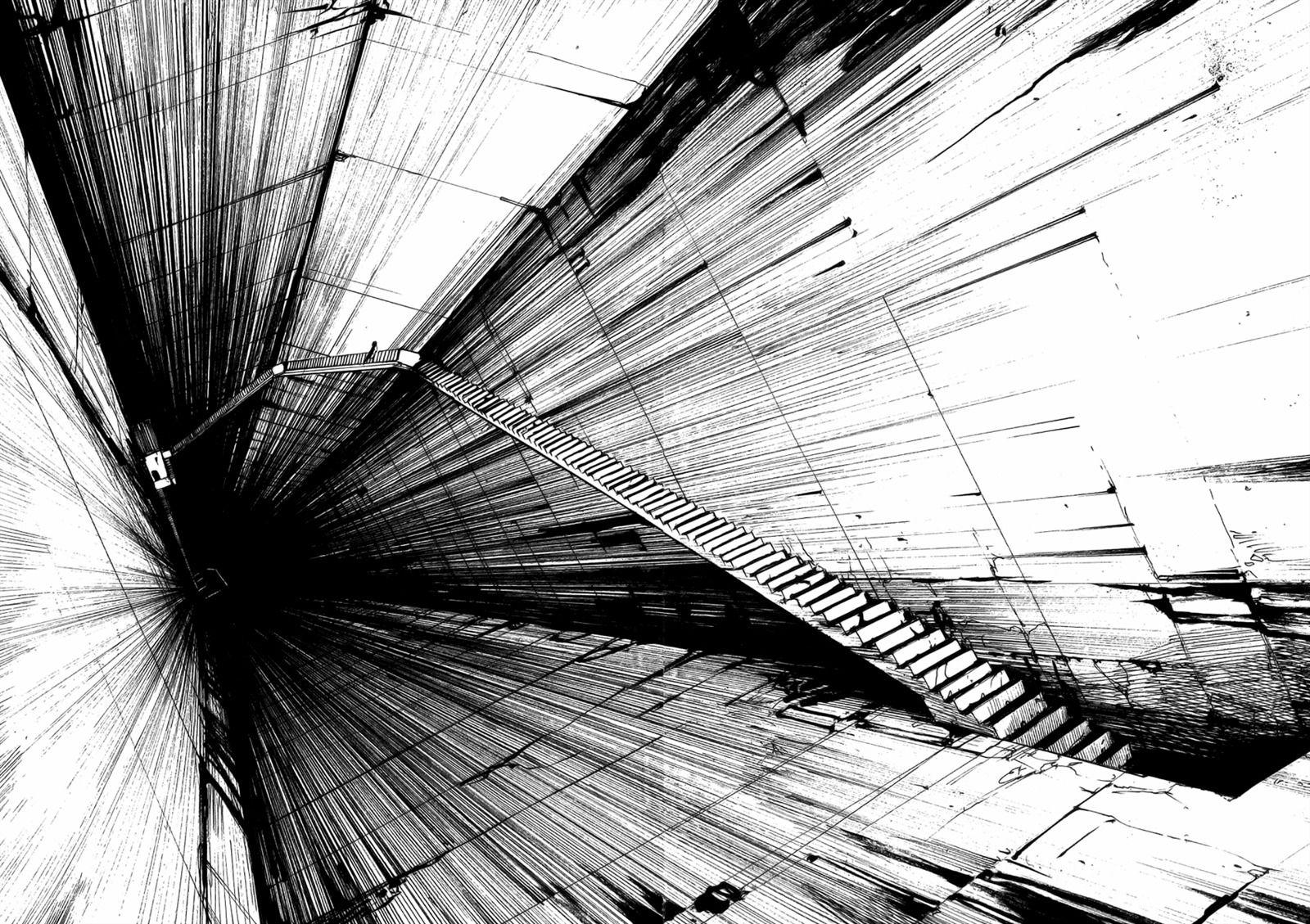

This is where the clearnet ends, and where the Darknet begins

From now on, you will only be able to access this website Anonymously (from the Tor Browser).

Click here from the Tor browser to access this website

The clearnet has become a corrupt Industry of Centralization and Censorship.

The Tor network IS the ideal place to be, as this is where you can't be censored, nor oppressed anymore.

It doesn't matter who you are, What truly matters is what you do.